Writing for Video Games – Part 2: The Process and Advice Professionals Wish They Received

The first part of our Writing for Video Games series featured stories and advice from three video game design professionals: Insomniac’s Mary Kenney, Graceful Decay’s Hanford Lemoore, and TiGames’ Isaac Zhang. The trio gave insight into the differences between narrative design and game writing, discussed how gameplay and story impact each other, and shared tips on getting into the field alongside stories of how they made it where they are today.

In this second part, they share advice they wish they’d had when starting out, discuss the process of editing, and dive into how different game genres determine how the writing is approached.

Teamwork is Key

“I wish I’d understood how collaborative the business of making video games is,” Kenney responds when asked what she wishes she’d known when starting out her career. Writing can be an isolated experience in many instances and Kenney’s experience was exactly that when she worked as a journalist. Then, her time traveling, researching, writing, and fact-checking was entirely solo. As a game writer, she came to love collaborating more than being a solo operator. “Pitching ideas and working with other creators is how I spend a lot of my time,” she says. “I love it, but it took me a few years to really be comfortable working on a team.”

Zhang’s advice is of the same spirit. “Be a part of the entire development team,” he says. “What you need to consider is not just sentence or audio-visual language, but also how it will adapt to the interactive experience.” There are unique rules that writers have to abide by in the game development process, like considering how the game’s camera moves around a character or being mindful that some players may skip cutscenes entirely. “But after you are used to writing the plot like weaving a web, brilliant ideas will come,” he concludes.

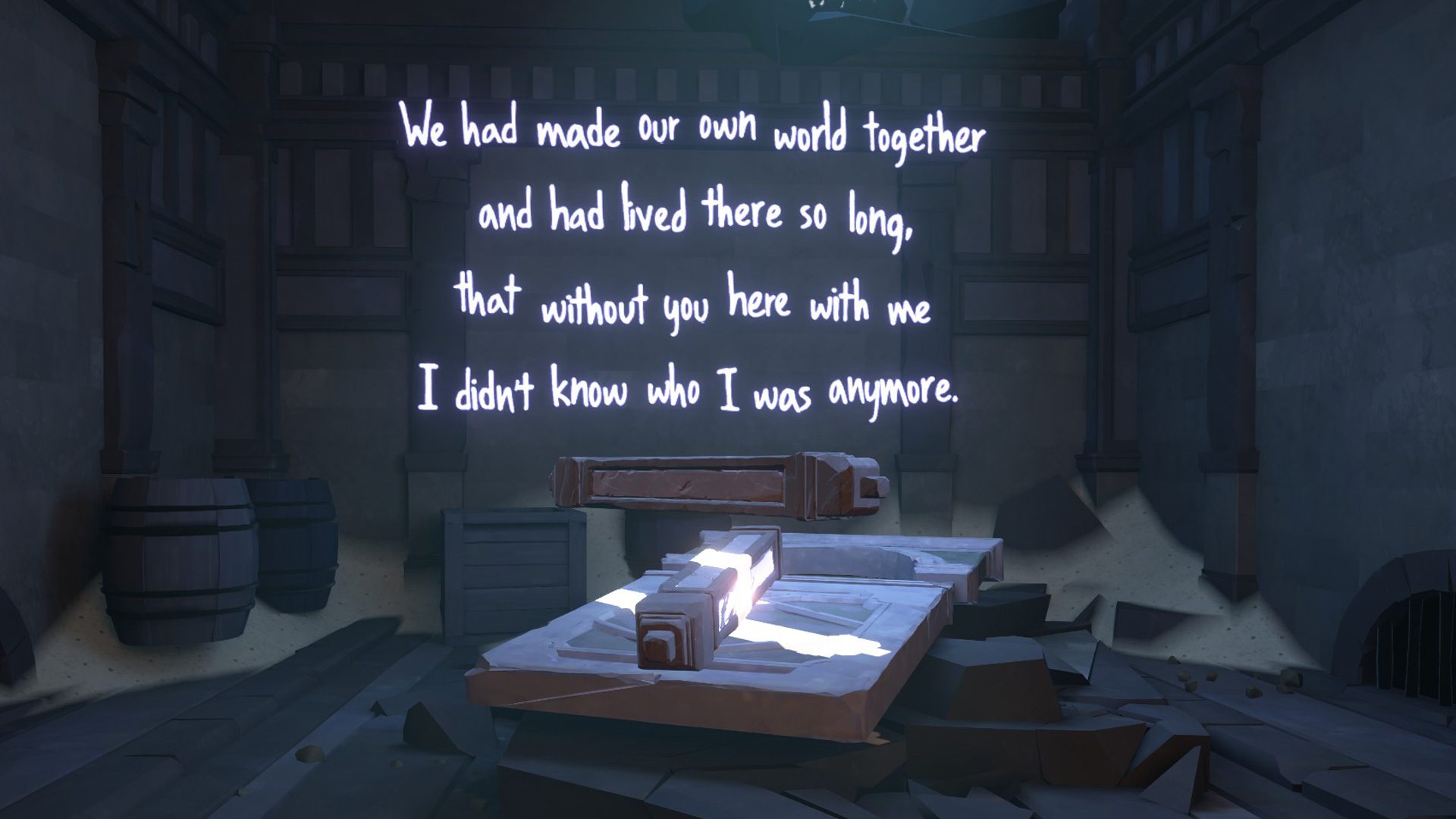

Lemoore’s experience with Maquette is a shining example of the multiple layers of collaboration that are possible on a gaming project even when centered on writing. He oversaw big picture issues, like how the story connected back to gameplay, while writer Gracie Gardner focused on character realism and dialog flow. When working with Bryce Dallas Howard and Seth Gabel, the actors who portray Kenzie and Michael respectively, Lemoore worked with the actors and incorporated their suggestions and rewrites to make the scenes even better.

“During recording, we had Bryce and Seth reading the script off of iPads from Google docs, and I had the script open as well on my PC,” Lemoore explains. “When the actors and I would talk through last-second script changes, I could update them in Google Docs and have it update on their iPads in real-time. It made these types of changes effortless. Having a writer on hand during recording for things like this, and having a way to get changes in front of the actors quickly, is invaluable to keeping the writing authentic.”

While Lemoore says he’s very happy with what the team ended up with, it wasn’t a perfect process. “I was a huge bottleneck because I was also directing the project, coding, and just doing lots of other stuff,” he says. Gracie Gardner, the playwright who wrote the script for Maquette, would often have ideas that Lemoore wouldn’t be able to vet to make sure they worked with the intricacies of the gameplay. “In retrospect, I really wish I had more time to dedicate to that.”

How Different Genres Impact The Process

With all the varying ways that studios are shaped and how different games are developed, it is no surprise that there’s no single answer for the difference between game writing and narrative design. This is equally true for the question of processes and it’s even more complex when you consider writing for different genres entirely.

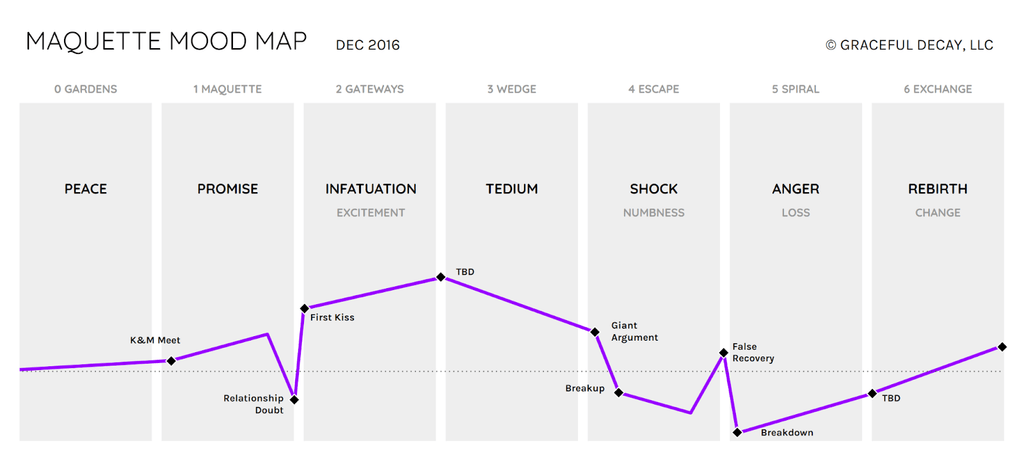

For the puzzler Maquette, Lemoore didn’t start working on the story until most of the puzzle development was completed. With the order of puzzles and level progression in mind, he then “looked at the content and correlated it to a ‘Mood Map’ that was outlined loosely based on a three-act structure.”

“I think it’s good to look at your game design and figure out how connected the story will be to playable elements in the game,” Lemoore says. “Does your story allude to puzzle solutions? Will the player need to know the story to solve the game, or can they skip over that stuff?”

Lemoore further explains that the team came up with answers to these questions early on as they wanted the game’s story to draw parallels to the recursive puzzles you’re solving, but without the story giving you explicit gameplay hints.

“The goal was to apply that consistently throughout the story,” he concludes. “And not lead the player to believe that a puzzle’s solution is buried in the last cutscene they watched, or the last bit of the letter they read, because we don’t want the player looking for something that isn’t there.”

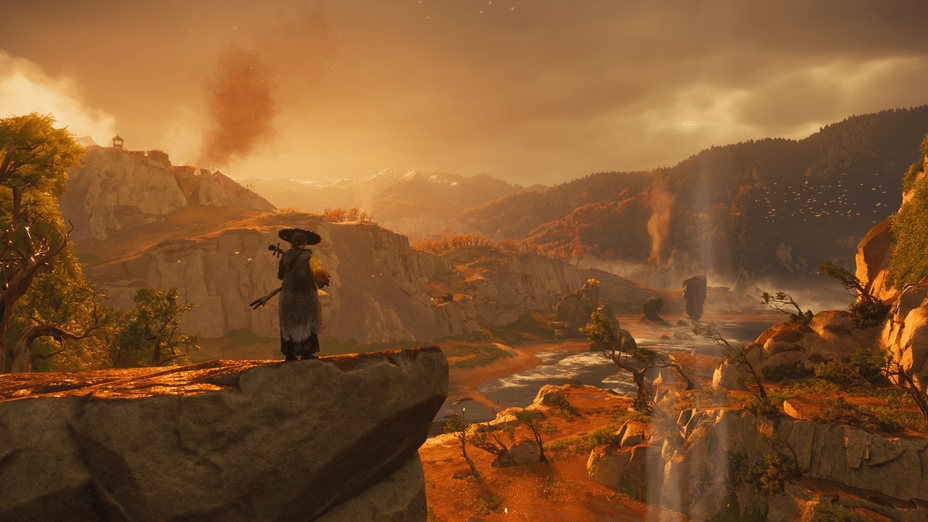

F.I.S.T. is a “Metroidvania” game, a genre of action-adventure video games focused on non-linear and utility-gated exploration and progression, so the level design is the core. Everything else in the game feeds into that. Zhang and the team decided on an “elegant starting point” and “exciting ending” at the start of the game’s concept design but he says “more details, especially the dialogue, was written only when they made significant progress on level design.”

“On that stage, the scale and the destination are concrete enough to make it possible to polish the narrative expression,” Zhang continued.

Insomniac’s Mary Kenney states that no matter the genre, the story needs to be engaging, with memorable characters and vivid moments. “The difference between gameplay genres is in the method of delivery,” she says. “I’ve worked on RPGs, single-player action-adventures, VR kid-friendly puzzles, and turn-based games with no voice-over. Each of them delivered a story in a different way: dialogue wheels, voice acting, codex entries, or with no ‘writing’ at all, just story beats and art that I nonetheless helped plot out.”

“It’s critical for a game writer to deeply understand the gameplay, pacing, and feel of a game they’re working on,” she continues. “You don’t need dialogue to tell a story, though that’s usually the first thing people think of when they think of game writing (and, don’t get me wrong, it’s a great part) — you need to understand what kinds of levels, obstacles, characters, and environments to place in front of the player to tell a story.”

The Key to Surviving The Editing Process

Editing and, especially so, cutting away some of your work is one of the biggest challenges that writers face. You’ve invested so much into the work and grown attached and, now, you’re told to remove these precious things. It’s tough, but Kenney says the transition from the first draft to the next is where the magic really happens. “There’s a saying that ‘the best writing is in the rewriting’ and it’s so true,” she says. “This is where ‘Oh God, is this gonna be good?’ transforms into ‘Hey, I think this is gonna be good’.”

“The tragedy is, of course, killing your darlings,” she continues. “Sometimes your favorite character beats or scenes conflict with something else in the story. Maybe a cutscene is too long, and players zone out and don’t get the info they needed. Maybe an awesome character beat in act 2 is coming too early and really needs to be saved until act 3. Maybe (and this one hurts) a side story is taking up too much of the spotlight that should be on the main story, so it needs to be cut entirely. Ouch.”

“The best piece of advice I can give here is to accept that many things aren’t cut because they’re bad, but because they don’t work in this story,” Kenney says. “Keep those characters, scenes, and beats close to your heart, and try to fit it into something else you make.”

Zhang and the team cut a lot away from F.I.S.T. so that players stayed engrossed in the game’s present. “We abandoned a great amount of the details of the characters’ past in F.I.S.T.,” he says. “ Things like how Torch City was taken over by the Legion, friendships for several of the main characters, Rayton’s depression as a result of a life of seclusion.”

These things would have enriched the story but Zhang feels they would slow down the hero’s journey. “However, we also consider it as an opportunity for us to create the next episode of the game if players are interested in it,” he adds.

Lemoore found that continuously evaluating the game’s overall vision softens the blow when cutting things. “Early on in my script, I wrote prefaces for each cutscene that explained what I was attempting to communicate, and why I made the choices I did,” he says. “It was a good first step in self-evaluation.”

Echoing Kenney and Zhang’s earlier sentiment, because something is cut doesn’t mean it is a bad idea. It just may not fit the current story. “There were a lot of things that got cut from the final version of Maquette, but I keep a folder for unfinished ideas, and I’m constantly adding to it, whether it’s a game idea, or a good turn of phrase, or just a note about a feeling I’m having that I’d love to capture in a story,” Lemoore says. “So it was not difficult for me to edit stuff out. The good ideas will live on.”