Friendly Competition in a Senior Living Community

How Sony Interactive Entertainment is Helping Support Physical Activity and Cognitive Health for Seniors

Sony Interactive Entertainment (SIE) and Sony Group Corporation are partnering with Sony Life Care Group*1, to offer a new avenue of physiotherapy to seniors living in long-term care facilities. A pilot project at Sonare Mejiro Otomeyama seniors’ residence in Tokyo, Japan, removes barriers to play with a video game that needs no controller or button-pressing of any kind—combining physical activity with interactive entertainment for seniors and people with disabilities.

*1 Sony Life Care, a subsidiary of Sony Financial Group Inc., owns and operates long-term care facilities in Japan.

Video games are already used in senior living facilities to promote physical and cognitive health. By emphasizing accessibility in design, Sony’s vision makes it easier for seniors to share in both fun and physical therapy, regardless of barriers of mobility or chronic pain.

“Physiotherapy Game” Pilot Project at Sonare Mejiro Otomeyama

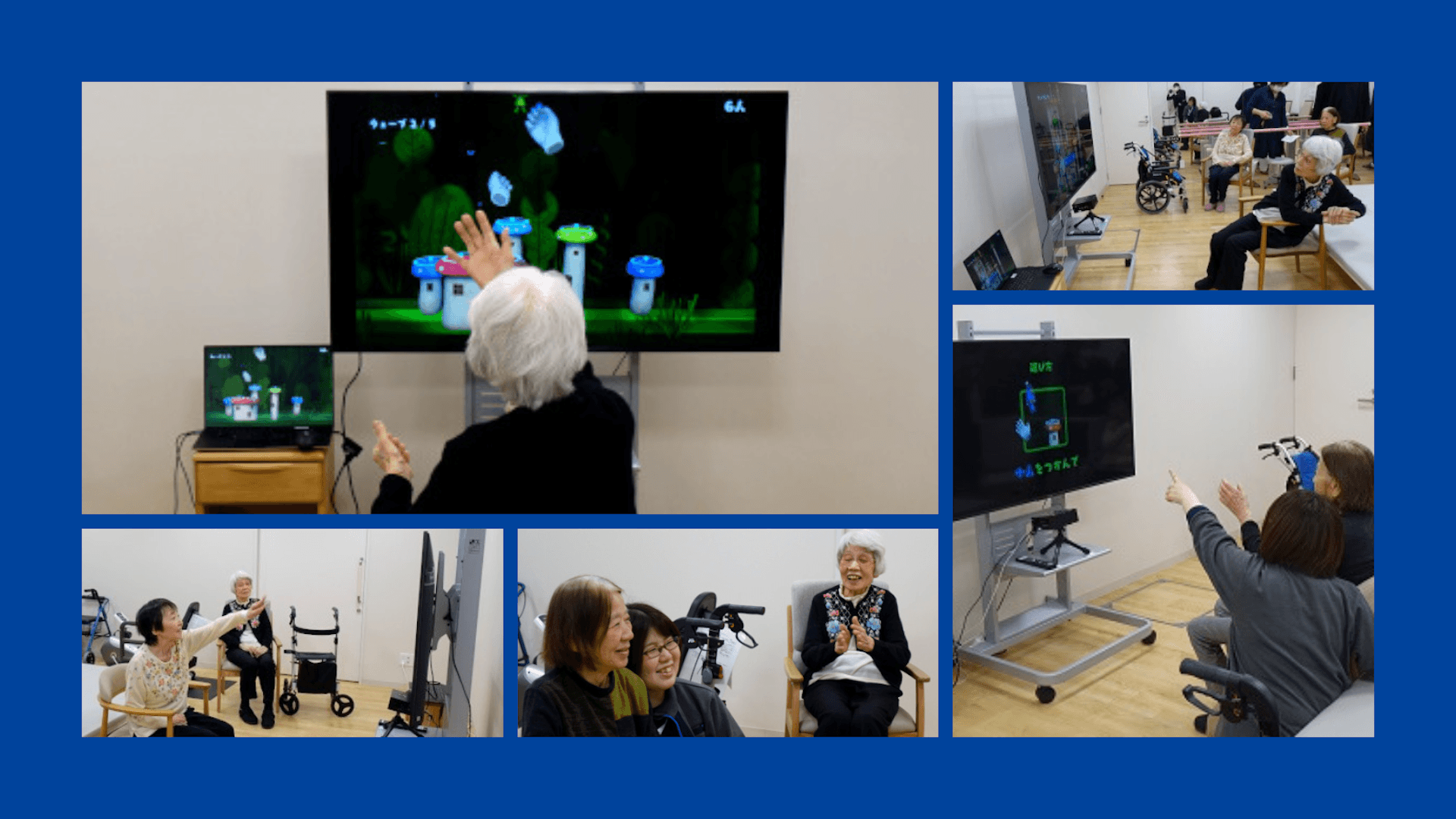

Mushroom Dwarf (Kinokobito), developed by SIE and Q-Games, starts by simply sitting in front of the monitor. The monitor is equipped with a camera that senses the player’s movements and begins the game automatically when a player sits down.

In Mushroom Dwarf, the “controller” is the player’s own hand. The camera recognizes the player’s gestures and mirrors them with an on-screen hand, which the player uses to catch falling dwarfs and place them atop a series of mushrooms. At the end of the game, players view their score and stats. Some players are becoming experts, playing almost every day and setting new high scores for home!

Kaori Takahashi, Occupational Therapist at Sonare Mejiro Otomeyama, was thrilled with the results of the pilot: “I am pleasantly surprised that enjoying games has naturally led to rehabilitation that expands the range of motion.”

Immobility and fine-motor issues are common for seniors living in long-term care facilities, Takahashi says. Games like Mushroom Dwarf encourage players to intuitively straighten their backs to see the screen, and to move their arms and upper bodies —as a result, the pilot project saw residents gradually expanding their range of motion. In some cases, seniors noticed improvement completing everyday tasks, like hygiene routines, through gradual redevelopment of strength through playing the game.

Takahashi found, too, that playing Mushroom Dwarf had a pleasantly surprising social impact on the community—encouraging discussion and friendly competition. Questions such as “did you play that game?” or “how many points did you get?” became common throughout the halls of Sonare Mejiro Otomeyama, Residents were given new topics of conversation and were able to build new relationships through play, and because Mushroom Dwarf is still being refined, players are being asked to share feedback for game developers. That sense of contribution is doing wonders for the social environment of the community.

“When it comes to rehabilitation, many people have the image of working in a room lined with specialized equipment, sometimes gritting their teeth, and of course that aspect will always exist,” Takahashi says. “But that’s why I feel that Mushroom Dwarf is a very good tool as an entry point for people to ‘enjoy’ rehabilitation.”

A New Way to Play

The pilot project adopts the principle of “Nothing to wear, nothing to hold, nothing to set-up.”

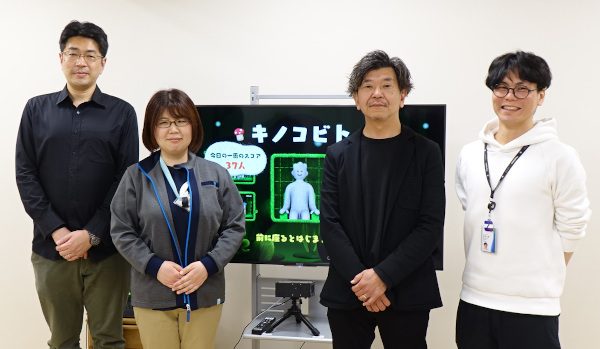

Goro Takaki from Sony Group Creative Center says the feedback from players and occupational therapists helps develop better rehabilitation games. “The Mushroom Dwarf project started as a new proposal sensing the data of body movements in collaboration with Sony Interactive Entertainment, and focused on rehabilitation, which is becoming a community issue as the population ages.”

Takaki continues, “Rehabilitation can be a painful experience. With this in mind, we changed our approach and got creative. We wanted to make rehabilitation fun, and restructure it in the form of a game. “Integrating play and rehabilitation—making it a desirable part of residents’ lives—is a different approach from regular rehabilitation.”

Naoyuki Miyada from Future Technology Group at SIE is developing new player inputs that don’t rely on controllers.

“We are conducting various trials to explore what kind of interaction is effective in reaching users other than core gamers,” says Miyada. “We discovered that there was a huge demand in the rehabilitation field, where it is necessary to move the body for smart cameras that recognize the movement of human, and the project began.”

Masanori Matsushima from Global Design Center at SIE says that the game’s art is an important part of the physical rehabilitation process, too. “Appearance is very important,” Says Matsushima. “By setting up a friendly design that players enjoy, rather than emphasizing the rehabilitation aspect, we can remove the mental barrier to rehabilitation.”

Matsushima continues, “It’s ideal if the players don’t think of the game primarily as rehabilitation. The residents who challenge themselves to reach new high scores every day experience Mushroom Dwarf as a game [rather than therapy], and that’s exactly what we intended.”

From Cutting Edge Technology to Community Service

Takaki envisions games like Mushroom Dwarf as part of a holistic approach to physical therapy and rehabilitation that will continue to evolve over time. “Since it is being developed as a tool for rehabilitation, we will continue to work on improvements with input from occupational therapists so that it can be used to treat a broad range of physical ailments.”

“In the future, I would like to develop the game into something available not just in long-term care homes and hospitals, but also in people’s homes. We would like to reach people who have difficulty accessing physiotherapy and use the Sony Group’s cutting-edge technologies to uplift our communities.”